Field Cooling Methods for Working Dogs

Heat injury is a serious risk for working and sporting dogs. High environmental temperatures plus heat generated through exercise can overheat these dogs. A dog’s core body temperature can easily reach over 105 degrees Fahrenheit during exertion. However, heat injury typically occurs only when physical activity continues and/or the dog’s ability to dissipate heat becomes compromised.

Definitions

Hyperthermia: increased core body temperature.

Heat stress: the initial pathologic response to increased core body temperature.

Heat injury: a sustained increase in core body temperature resulting in changes in physiologic function and mild to moderate organ damage.

Heat stroke: heat injury with neurologic signs and organ damage.

The American College of Veterinary Emergency and Critical Care (ACVECC) recommends the strategy of ‘cool first, transport second.’ Handlers should immediately begin cooling a dog showing signs of heat stress and then transport to a veterinary facility. Current effective cooling methods include:

-

Providing rest and shade

-

Immersion in cool water or wetting the dog’s skin and using a fan to increase air circulation around the dog

-

Wetting the paw pads with isopropyl alcohol

-

Placing ice packs in the armpits and groin

There have been few scientific studies to compare these various cooling methods and confirm the best approach for cooling dogs with exertional hyperthermia. One must also recognize that access to water may be limited in working environments, eliminating the option of full-body water immersion for over-heated dogs. To find answers and improve outcomes for at-risk dogs, the AKC Canine Health Foundation (CHF) awarded funding for a pilot study conducted at the Penn Vet Working Dog Center. Investigators compared four different cooling methods to assess their effect on core body temperature after exercise in working dogs.

Study Methods

The cooling strategies examined were:

1) Ice packs around the dog’s neck

2) A water-soaked towel around the dog’s neck

3) A water-soaked towel in the dog’s armpits (axillae)

4) A voluntary head dunk into tepid water (70 degrees Fahrenheit)

Participating dogs were exercised by doing warm-ups and recalls until their core body temperature reached over 105 degrees Fahrenheit or until they showed two or more signs of heat stress. They participated in one of the cooling strategies for 30 seconds and were monitored for 40 minutes. Over four weeks, each dog participated in all four cooling methods. (Water immersion and other cooling methods were used for any dog whose core body temperature exceeded 107 degrees Fahrenheit or whose core body temperature remained over 103 degrees Fahrenheit after 40 minutes.)

Study Results

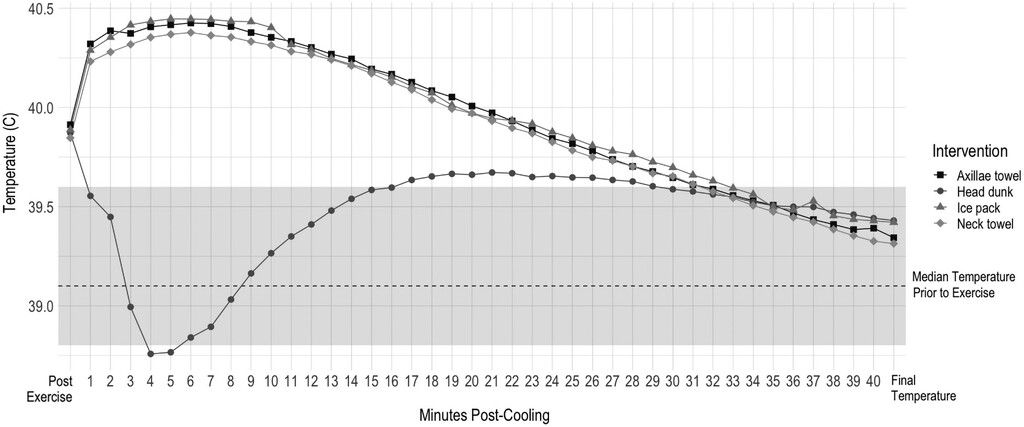

All four cooling protocols successfully returned the dogs’ core body temperature to baseline after 40 minutes. However, only the voluntary head dunk behavior lowered core body temperature in the first 30 seconds and created a lower body temperature during the rapid cooling period in the first 5 minutes after intervention (See Figure 2 from Parnes et al).

Investigators suggest several physiologic factors that may explain the superior results following a voluntary head dunk in cool water. When a dog experiences heat stress, blood vessels dilate in the muzzle, ears, and limbs, increasing blood flow to these peripheral areas where heat can dissipate through convection and radiation. The skin on a dog’s head is also relatively thin compared to other parts of the body, allowing for more rapid heat exchange from this region. Finally, blood in the nasal cavity is cooled by airflow before it travels to the brain, providing yet another way of protecting the brain from heat injury. For all of these reasons, cooling methods that target a dog’s head and neck may be most effective at reducing the core body temperature and preventing heat injury.

Teaching the Voluntary Head Dunk

To use the voluntary head dunk method in the field, dogs must first be trained to retrieve a toy or piece of food from the bottom of a bucket of water.

Click here for a voluntary head dunk training demonstration.

It is important to note that this cooling method can only be used for dogs with a normal mental status who are willing to participate and can stop panting long enough to dunk their head. If any dog is not mentally appropriate, emergency cooling measures and rapid transport to a veterinary facility are required.

This study provides critical and actionable insights into the best methods to cool a dog with exercise-induced hyperthermia in the field. Future studies can review additional cooling strategies helpful to canine handlers such as the effect of pouring water over a dog’s head, adding a fan to improve airflow, and the effect of intermittent cooling activities during work. CHF and its donors will continue to support valuable health research like this study and provide evidence-based recommendations to safeguard the health of all dogs. Learn more about this work at www.akcchf.org.

Related Articles

Help Future Generations of Dogs

Participate in canine health research by providing samples or by enrolling in a clinical trial. Samples are needed from healthy dogs and dogs affected by specific diseases.