Canine Epigenetics and Aging

We all want to live a long and healthy life. Likewise, we want our dogs to live the longest, healthiest lives possible. The study of aging, known as gerontology, is an active area of health research for humans and canines. Mapping of the human and canine genomes and continued advancements in genetic technology provide new areas of exploration into how we age and our susceptibility to diseases as we get older. AKC Canine Health Foundation (CHF) funded researchers have investigated the role of epigenetics in these processes in dogs.

An organism’s phenotype, defined as its observable characteristics such as blue eyes or curly coat texture, is determined by its genetic make-up and the environment. Epigenetics is the study of phenotype changes that do not involve altering the sequence of DNA nucleotides. In other words, it examines the factors that affect gene expression and allow organisms with the same genetic sequence to look and behave very differently.

|

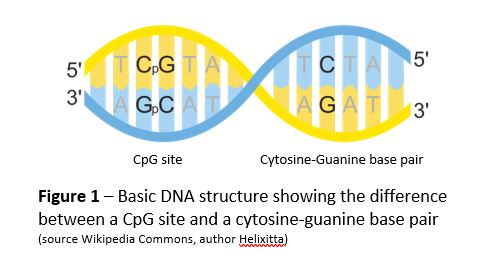

DNA is made of nucleotides. Each nucleotide consists of a sugar (deoxyribose, denoted by the curved lines in Figure 1), one of four bases, and a phosphate. The four bases are cytosine (C), guanine (G), thymine (T), and adenine (A). Cytosine always pairs with guanine and thymine always pairs with adenine to hold the two strands of DNA together. |

|

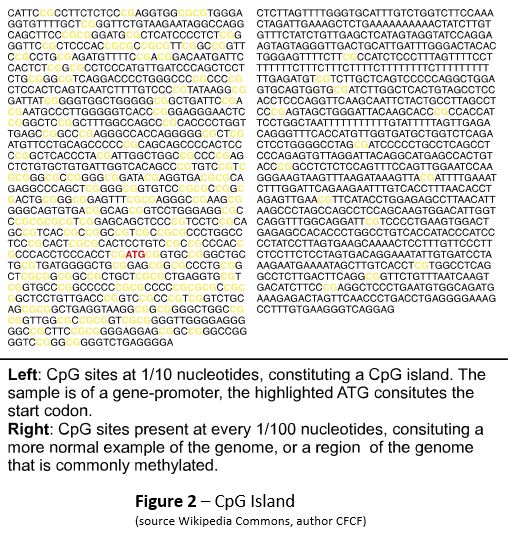

DNA methylation is one mechanism the body uses to control gene expression. It occurs when enzymes transfer a methyl group to the cytosine nucleotide at a CpG site. CpG sites occur when cytosine follows guanine along the five prime to three prime strand of DNA (Figure 1). They are relatively rare in the vertebrate genome, but occur in clusters, or islands (Figure 2), and often indicate the start of gene promoter regions, the areas where transcription is initiated on the strand of DNA.

The goal of CHF Grant 01822: Beyond the Genome: The Intersection of Genes and the Environment in Canine Cancer, was to establish the techniques and methods needed to define normal methylation in a variety of domestic dog breeds. Once these methylation patterns, or methylomes, were described, the next step would be to explore how gene regulation via methylation affects phenotype, disease, and health.

A canid epigenetic clock –

Phase one of this project was the development of an ‘epigenetic clock’ for dogs. The epigenetic clock estimates an organism’s molecular age based on DNA methylation levels. In humans, overall methylation levels decline with age and correlate with age-related disease. Researchers receiving CHF grant support at the University of California, Los Angeles examined a subset of CpG sites in 46 dogs, 62 gray wolves (part of the wild population in Yellowstone National Park), and 729 humans. They compared the methylation data from these sites and each organism’s chronologic age to create an epigenetic clock for dogs. While the correlation between age and methylation levels in dogs or wolves independently was not statistically significant (likely because of the small number of dogs studied), examining the combined dog and wolf data did show a strong linear relationship between epigenetic age and chronologic age for canids, similar to that found in humans.

Epigenetic age acceleration –

In humans, an increasing difference between epigenetic age and chronologic age is associated with many diseases. For example, a 46-year-old malnourished human exposed to smog will have a much higher epigenetic age and disease risk than a 46-year-old eating a balanced diet and not exposed to air pollution. Does the same hold true for dogs? Researchers hypothesized that since large breed dogs have a shorter lifespan than small breed dogs, in general, their epigenetic age should outpace their chronologic age and canine epigenetic age acceleration should correlate with dog breed size. While they were unable to demonstrate a statistically significant correlation between age acceleration and breed weight in this small population, the idea provides an interesting way to explore the effects of breed size on aging in a population as phenotypically diverse as the domestic dog.

More to explore –

This research, published in the journal Aging1, demonstrates that DNA methylation and epigenetic aging in dogs resembles that in humans. With an epigenetic clock established for canids, scientists can estimate the chronologic age of an individual from a DNA sample and have another tool to suggest the individual’s risk of disease. Further study can examine the effects of sex, breed size, drugs, and diet on epigenetic age in dogs. The great news is that epigenetic modifications, such as DNA methylation, can be reversible. Therefore, researchers may find methods to alter aging and the development of diseases such as cancer in humans and dogs. CHF has awarded two grants to study such DNA methylation patterns in one canine cancer, lymphoma: 02309-T: Targeting the Cancer Epigenome: The Effect of Specific Histone Lysine Methyltransferase Inhibition in Canine B-Cell Lymphoma; and 01918-G: Discovery of Biomarkers to Detect Lymphoma Risk, Classify For Treatment, and Predict Outcome in Golden Retrievers. Stay tuned as CHF and its donors work toward this bright future where we, and our dogs, enjoy longer, healthier lives.

1. Thompson, M. J., vonHoldt, B., Horvath, S., & Pellegrini, M. (2017). An epigenetic aging clock for dogs and wolves. Aging (Albany NY), 9(3), 1055-1068.

http://doi:10.18632/aging.101211

Help Future Generations of Dogs

Participate in canine health research by providing samples or by enrolling in a clinical trial. Samples are needed from healthy dogs and dogs affected by specific diseases.